Nearly everyone’s life has been punctuated by a financial emergency: That time when you desperately needed cash you didn’t have.

For my wife and me, that moment arrived, unannounced, eight years ago. My son contracted an exotic disease with an unpronounceable name and spent a week in the hospital. Thankfully, and most importantly, he fully recovered. However, we found ourselves punched in the gut by one of the most stressful financial predicaments we had ever faced.

“OUR SON IS EXAMINED IN THE EMERGENCY ROOM PRIOR TO BEING ADMITTED FOR A RARE DISEASE.”

We had insurance that covered the bulk of the bill. But the insurance deductible — the amount we had to pay out of pocket — was over USD$3,000. Maybe we could have managed that … but sometimes you’re just unlucky and multiple, major financial costs come all at once. That’s what happened to us. The month before our son got sick, a USD$3,000 car repair bill drained our bank account. And, because his hospital stay straddled the calendar change from December to January, we had to cover that USD$3,000 deductible for two years — meaning we paid USD$6,000 in deductible alone. On top of that, there were hospital costs that our insurance didn’t cover.

We just didn’t have the money.

You probably have a similar story, though the details may vary: The car you depend on for commuting to work calls it quits; the livestock your family relies on for income dies unexpectedly; your spouse is laid off from the part-time job that helps pay for your kids’ schooling. Except for the world’s wealthiest, almost everyone — regardless of geographic location or their rung on the economic ladder — has faced the stress and hardship of a financial emergency.

In situations like these, being able to acquire extra money in a matter of days can be the difference between holding onto or losing your home, eating or going hungry, and — in extreme cases — surviving or dying. Yet how many people around the world are actually able to access the necessary emergency funds to keep them afloat? And how do they do so?

FINANCIAL INCLUSION

The World Bank’s 2014 Global Findex survey — the most extensive global financial survey conducted, polling more than 150,000 people in 140 countries — examines this issue as an aspect of financial realities around the world.

The survey asked adults if, in an emergency, they could come up with a specific amount of money within one month. The amount was adjusted across economies, so that it represented a similar share in each country, giving the World Bank the ability to compare broadly how easily people could acquire money in a pinch.

Only 31% of respondents said they thought it would be “very possible” to come up with the funds. Another 31% stated it would be “somewhat possible.”

The Global Findex also addressed a related question: What percentage of adults globally have a bank account or other formal financial account of some kind?

The World Bank asked these questions because the concept of “financial inclusion” — whether or not people participate in the formal banking system — is at the heart of the World Bank’s Universal Financial Access 2020 initiative, known as UFA2020.

The World Bank’s core premise around UFA2020 is that being “financially included” makes individuals more financially resilient and helps alleviate poverty. The initiative was sparked by an annual gathering of banks, credit card companies, microfinance institutions, multilateral agencies, and telecommunications companies, hosted by the World Bank in 2015.

The goal of UFA2020 is to give adults everywhere, but especially in 25 specific countries where 73% of the world’s “unbanked” reside, access to the formal financial system so that they have a vehicle to save money, pay bills, receive payments, and get credit. Fourteen agencies, including banks, microfinance companies, and corporations like Visa and MasterCard, have signed on to partner with the World Bank in order to bring these 2 billion unbanked into the world’s formal financial structures.

A HOMEOWNER IN THE PREVENTÓRIO FAVELA OUTSIDE OF RIO DE JANEIRO SURVEYS THE DAMAGE DONE TO HIS HOME FROM A LANDSLIDE. IN EMERGENCIES LIKE THIS, PEOPLE IN BRAZIL REPORT HAVING A HARD TIME COMING UP WITH FUNDS.

SO, WHAT DOES THIS DATA TELL US?

The Global Findex reveals that 38% of adults don’t have a formal financial services account of any type; they aren’t “financially included.” Considering large rural areas in the world where banking centers aren’t found or are limited in number, this number doesn’t sound too alarming.

The Orb team became curious about how these two issues — access to emergency funds and financial inclusion — intermingled. If being “included” supports an individual’s financial resilience, how were people supported by these formal structures when they were in the direst financial need — when they were living through a major financial shock? How did the global percentages of people with bank accounts and their ability to access funds in an emergency stack up?

We wanted to dig deeper into the Global Findex data, so we partnered with Toronto-based statistical analytics firm, Datassist. Using the detailed information about each individual in the Global Findex data we combined Orb’s journalism and investigative skills with Datassist’s statistical analysis capabilities and built a model designed to predict a person’s likelihood of being able to raise the necessary emergency funds.

At a broad level, one third of people who said they could readily come up with funds were doing so without the support of formal banking structures. Furthermore, of all the people who indicated that they could not come up with the emergency funds (responding “somewhat possible” or “not very possible”), one third of them said they actually had some type of formal financial account.

So, while having an account does seem to make a difference, if being brought into the formal banking system is supposed to underlie an individual’s financial resilience, the outcomes don’t align the way we’d expected.

Along with a person’s access to the formal financial system, we wanted to explore what effect other factors — such as gender, education and income levels — might have on an individual’s ability to get emergency funds.

Among those four factors, the strongest predictor of the ability to raise emergency funds is a person’s level of education. The second most important is income. The third is whether or not an individual is participating in the formal financial system. Gender ranks fourth.

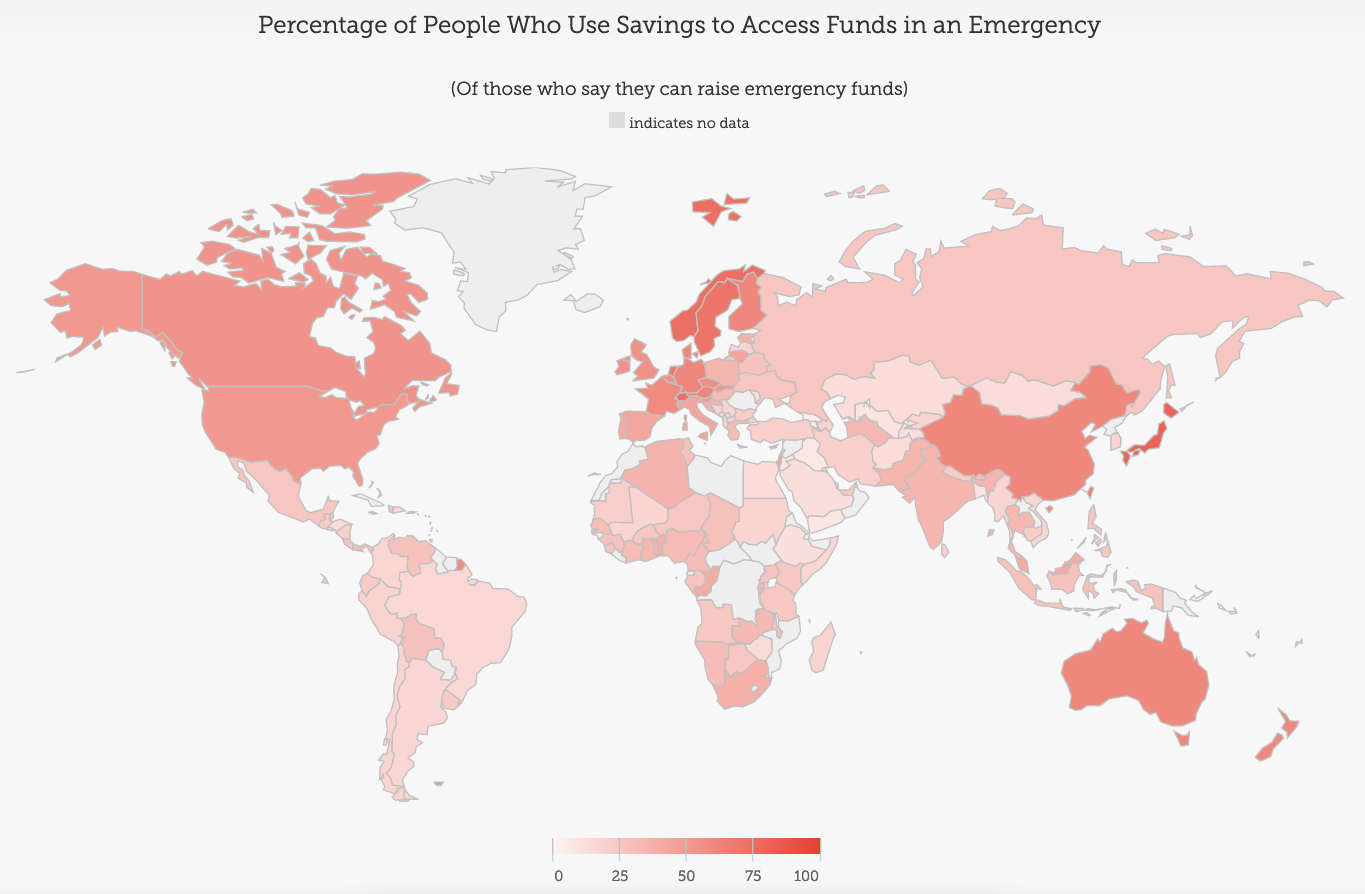

After we assessed if a person could come up with emergency funds, we examined the data in the 2014 Global Findex about how they would come up with the funds.

If you look closely at the survey results, they reveal that people living in East Asia, the Pacific, and high-income countries that are part of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) likely have the money saved (though where they have it saved is still a question).

But for the rest of the world — and that’s a lot of people — adults who reported that they could access emergency funds mostly received them through a very “informal” network: Family and friends. A small percentage of people indicated that they were able to get funds or a loan from their employer, or by working more hours.

These survey results speak to how my wife and I solved our own financial crisis. We had used all our savings to cover the auto repair bill. We considered paying the insurance deductible with our credit card, but we didn’t have enough available credit to cover the entire bill and we were concerned that our credit score would be negatively affected if we maxed out the card. Limp and defeated, we succumbed to asking family for help.

IN A CAMBODIAN FISHING VILLAGE OUTSIDE OF SIEM REAP, BOYS PLAY ON THE HARD PACKED MUD. A SEVERE DROUGHT HAS PLAGUED THE COUNTRY AND CHALLENGED THE INCOMES OF THE LOCAL FISHERMEN. MANY GET LOANS TO COVER BASIC LIVING FROM LOCAL MONEY LENDERS.

WHERE WE’RE GOING…

Orb is reporting a feature story on where people around the world get money in an emergency. We began looking at where we might go to learn more and enrich our understanding about what’s happening for people on the ground.

To that end, the Orb team continued our work with Datassist to determine which countries would be the most interesting and informative to visit for on-the-ground reporting — the phase of the project when we visit a country and allow personal stories and encounters to shape our understanding. By aggregating the predictions at the country level, we were able to estimate what percentage of a country’s population would likely be able to access emergency money.

Then came the fun part. We compared the predicted results with the actual responses (for example, were people in countries that have a high likelihood of acquiring emergency funds actually able to get them?) in the Global Findex and identified countries with the largest gap between the two.

We wanted to understand this gap. What are the other factors — besides being “financially included” — that support an individual’s financial resilience, especially during a financial shock? How do those other factors function and interact? Are they purely around social networks? Or are there structures that can be fostered and replicated? Where do they work best and what might we learn from them about supporting an individual’s resilience in the face of a financial shock?

The list of countries whose survey responses differed most greatly from the predictive model Datassist built would be the countries where other factors — like community banks, informal money lending and the black market — were most powerfully at play.

We followed where this data led to identify the countries we’d visit for our reporting.

Out of 143 countries, 36 had an actual rate that was less than our predictions by 10% or more. Most of those 36 countries are low-income countries. But one near the top, Brazil, is not.

COUNTRIES WHERE ABILITY TO RAISE EMERGENCY FUNDS DIFFERS FROM ORB'S PREDICTION

The following tables highlight how some countries actual survey responses differ from the performance our model predicts. Each table shows the following attributes:

Name of country

Actual percentage of respondents from the Findex survey who said it was "Very possible" or "Somewhat possible" to raise emergency funds

Predicted percentage given the model we built

The difference between these columns: Actual minus Predicted

Countries with a large positive difference are those performing better than our model predicts. Countries with a large negative difference are those performing worse than our model predicts.

Top 10 countries - Those whose actual response is furthest above the model's predictions

| Country | Findex actual response % | Model predicted % | Difference (Actual - Predicted) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myanmar | 90.3% | 47.9% | 42.5 |

| Turkmenistan | 81.4% | 51.8% | 29.6 |

| Niger | 69.5% | 45.5% | 24.0 |

| Cambodia | 68.9% | 46.6% | 22.3 |

| Uzbekistan | 79.8% | 57.9% | 21.9 |

| Bolivia | 75.6% | 55.3% | 20.3 |

| China | 75.2% | 57.4% | 17.8 |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 72.8% | 56.6% | 16.3 |

| Israel | 88.0% | 72.2% | 15.8 |

| Algeria | 71.2% | 55.5% | 15.7 |

Bottom 10 countries - Those whose actual response is furthest below the model's predictions

| Country | Findex actual response % | Model predicted % | Difference (Actual - Predicted) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Findex actual response % | Model predicted % | Difference (Actual - Predicted) |

| Namibia | 23.5% | 58.3% | -34.8 |

| Zambia | 30.0% | 59.3% | -29.3 |

| Sri Lanka | 34.1% | 62.0% | -27.9 |

| Portugal | 41.4% | 67.5% | -26.1 |

| Hungary | 39.5% | 64.1% | -24.6 |

| South Africa | 40.3% | 63.8% | -23.6 |

| Angola | 28.1% | 51.2% | -23.2 |

| Brazil | 35.5% | 58.0% | -22.5 |

| Togo | 28.1% | 50.6% | -22.5 |

| Turkey | 40.9% | 63.1% | -22.2 |

Home to the world’s seventh-largest economy and a growing middle class, Brazil is a country where few people report being able to come up with emergency funds even though roughly 60% report having a formal financial account.

Since 2010, Brazil has been a member of the Alliance for Financial Inclusion, a consortium of monetary policy makers from developing and emerging countries who are working toward financial inclusion for the poor. Brazil is also one of the World Bank’s 25 target countries as part of the UFA2020 initiative. So, with all this attention to including Brazilians in the formal financial systems, why aren’t more Brazilians able to access funds in an emergency? Shouldn’t the country be a model case for the “promise” of financial inclusion? These questions lay the foundation for our reporting work in Brazil and around the world.

Counter to what we found happening in Brazil, there were several countries that reported easier access to emergency funds than the model predicted. With a couple of exceptions, they were low-income countries.

Myanmar topped the list. Myanmar residents responded they could get emergency funds much more easily than our statistical model predicted. Nearly 88% said it would be “possible” or “very possible” to get the required funds. This is one of the highest rates in the survey — nearly 40% above our prediction. Increasing our interest in the country, fewer than one quarter of those who said they could get funds in Myanmar report having a financial account of any type.

OUTSIDE OF RIO DE JANEIRO, A HOMEOWNER CLEANS UP AFTER A FLOOD IN HIS HOME LOCATED IN THE PREVENTÓRIO FAVELA. LACK OF ACCESS TO BANKS FOR PEOPLE LIVING IN FAVELAS HAS LED TO A SURGE IN COMMUNITY BANKS. THESE BANKS HAVE THEIR OWN CURRENCY SO THE MONEY STAYS AND GROWS IN THE FAVELA. GIVING PEOPLE GREATER ACCESS IN TIMES OF EMERGENCY.

Existing academic research shows that, in countries like this, loans are often distributed through networks of friends, family, and independent moneylenders. Researchers sometimes call the sum of these networks a country’s “indigenous” or, more typically, “informal” financial sector.

When we pull back the lens and look at the Global Findex as a whole, almost regardless of the country, men said they could get money more easily than women, formal financial system account holders more easily than non-account holders, educated people more easily than non-educated people, and wealthier people more easily than their poorer counterparts.

But when we looked at where these factors were the weakest predictors of whether a person could get emergency funds, many of the same countries kept coming up: Myanmar, followed by Turkmenistan, and Niger.

Could it be that these countries’ financial systems (formal or not) are unusually good at getting money into the hands of women, less educated people, and the poor, and that’s why they beat our model by such a wide margin? This is just one of the many questions that will guide our reporting.

Orb’s team of professional journalists kicked off the on the ground reporting in Brazil to better understand both why people there have a harder time than expected coming up with emergency money and how informal banks are rising to meet this problem. In Cambodia and Myanmar, we are exploring how it is that people in these relatively poor countries can come up with money so easily, given their low rates of financial inclusion and education. And in the United States, we are reporting on a recent survey conducted by the U.S. Federal Reserve that indicates that 47% of Americans would have a hard time coming up with USD$400 within a month. How is it that in a wealthy super power with a financially included population so many people have a hard time coming up with funds in an emergency?

While there are many questions yet to be answered, one thing is clear from Orb and Datassist’s original data analysis: No one, save the world’s wealthiest one percent, is immune to financial emergencies.

Financial emergencies arrive unexpectedly and are a source of major stress and grief. With roughly two thirds of the global population surveyed saying it is “somewhat possible,” “not very possible,” and “not possible” to come up with funds in an emergency, it is obvious that being counted among the “financially included” is not the only way to be prepared for a financial emergency.

JOIN US

We want to hear about your personal experience with financial shock.

The more input we have from you — the public — the better Orb’s understanding of the diversity of experiences will be and the richer our reporting will be to better serve you.

Contribute to our social journalism:

1) Message us on Facebook with the keyword FinancialShock in the body of the message to complete a short survey. At the end of the survey you will have the option to submit a photo that represents how you were, or were not, able to access emergency funds.

2) Tweet us @OrbTweet using #OrbFinancialShock and #OrbCommunity with a response (and photo) to one or both of these questions:

Does your culture or religion matter when it comes to weathering a financial emergency?

How does your religion or culture affect your financial philosophy?

Responses will be aggregated on our community page to show where the conversation is going and unite us around our human story.

We will learn from you and we hope you can learn from us. Thank you for your contribution. You’re helping us tell a stronger and more compelling story.