Excess Baggage

Is There Room for Families in the Global Labor Trade?

An Investigative Report By: Pierre Kattar, Journalist, Email and Alex Park, Journalist, Email

CHAPTER 1THE WORLD GOES TO WORK

If you live in a developed country, chances are good that the people who clean your office or home, stock the shelves at the local store, or clear your plates at the neighborhood restaurant, were born in another country. If you live in a developing country, it’s likely that someone in your community has crossed a border (or an ocean) for a job, and has sent back money to support an economy you rely on. During the last four decades, the number of international migrants has nearly tripled. Almost a quarter of a billion people live in a country different from the one in which they were born.

In the past ten years, immigrants accounted for nearly half the increase in the American and 70 percent of the European workforce. Many countries in North America, Europe, and Asia have created legal channels for foreign workers. As these countries’ birth rates decline, they will need not just foreign workers, but their children as well. Yet from country to country, governments treat the children of foreign workers as an unwanted burden. Frequently, the children of migrants have become part of a disconnected generation, brought to a strange land where they are unsure how to claim a place, or left at home because their parents cannot accommodate them abroad.

The Philippines is especially familiar with these trade-offs. Since the 1970s, the Philippine government has embraced the global labor trade as a means to national development, even calling departed citizens “national heroes” for their sacrifice. In 2013, more than 2.3 million Filipinos went abroad to work. Remittances from this army of laborers accounted for more than 10 percent of the country’s GDP. The government has even established dedicated agencies to place workers abroad and monitor their safety overseas.

Despite an impressive infrastructure, the government of the Philippines, or any sending country, can only do so much to prepare citizens for a life abroad. In a system which prioritizes the placement of workers, children are a secondary consideration. Children who join their parents abroad often arrive without a clear way to become part of the new society. But even bringing children to live with them in a new country can be a hurdle for migrant parents. Often, destination countries create barriers for parents to bring their children to the country at all.

WE’RE ASKING YOU

CHAPTER 2THE PRICE OF FAMILY

With its population aging, Finland is desperate for immigrants to come and fill essential jobs. In the capital, Helsinki, cleaning jobs are largely taken by foreign workers, many of them Filipinos. Janet Andog is a cleaner who has lived in Finland since 2008. While the country made it easy for her to come and work, the problems she encountered when she tried to reunite her family illustrate Finland's lack of interest in accepting immigrant children.

As she said above, Janet’s first attempt to bring her children to Finland, in 2011, forced her to take on an almost unbearable work schedule. But difficult as her first and ultimately failed attempt was, Janet’s second attempt to sponsor her family was harder still. In 2014, Janet briefly returned to the Philippines and became pregnant. After her third child was born in Finland, she had to prove an income of 34,560 Euros after taxes to sponsor her entire family.

“This is more than the average Finn earns,” says Lena Näre, the sociologist at Helsinki University. “An average Finn couldn’t afford a family if this same standard was applied to them.”

To meet the requirement, Janet asked her husband, Danilo, to join her in Helsinki, temporarily leaving the children in the care of relatives. Only with their combined incomes could Janet meet the burden required to bring all three children to live with her.

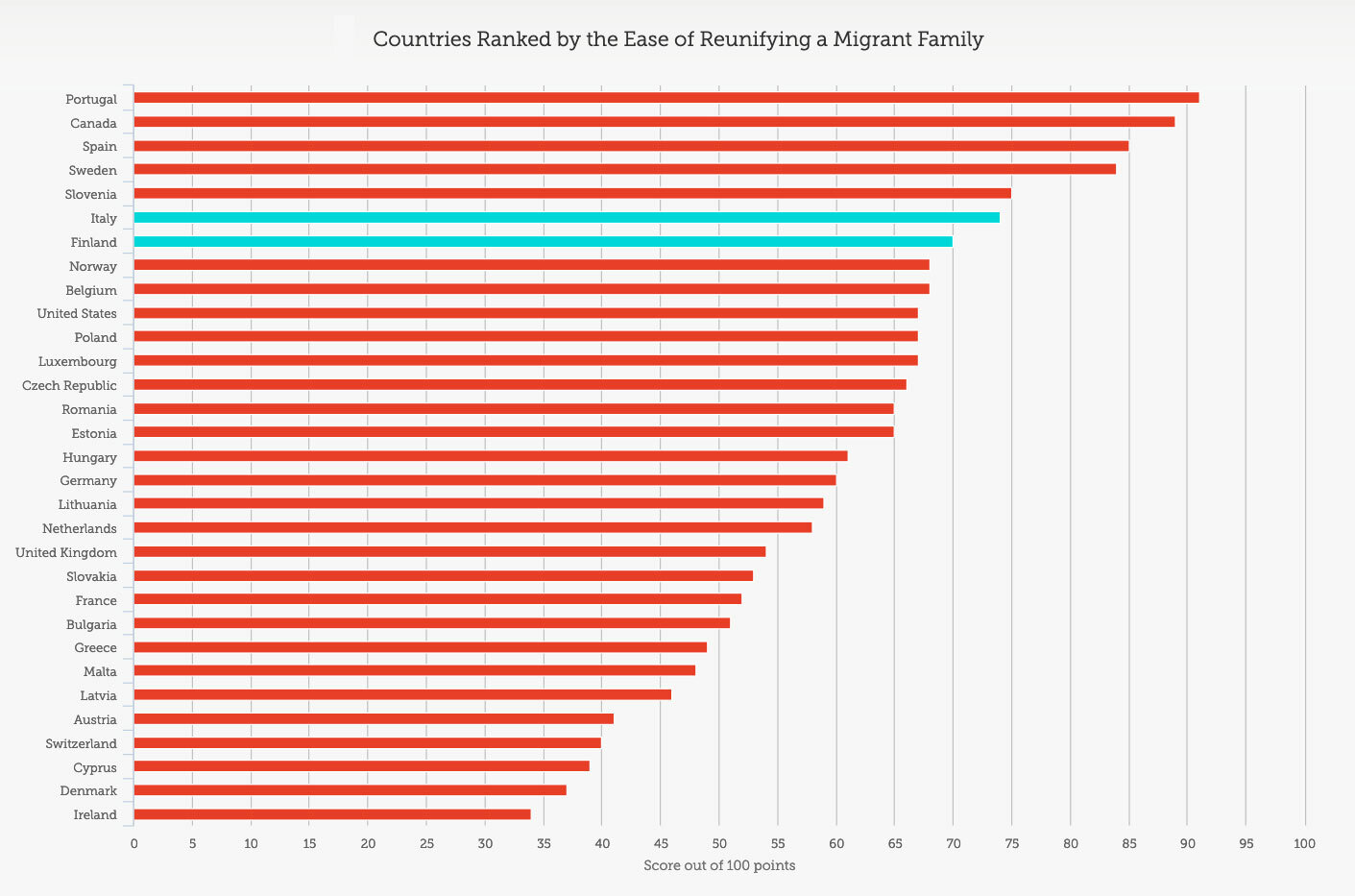

Despite its high income requirement, sponsoring migrant children is easier in Finland than in many other destination countries. To compare the relative ease or difficulty of reuniting a family in European and North American countries, the Migration Policy Group in Brussels and the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs have developed a system for scoring and ranking countries by their family reunification policies. With a score of 70 out of a possible 100 points, Finland is the seventh highest ranked country in this category.

In Ireland, the lowest-ranked country on the Mipex index, the immigration service is required to deny entry to family members who would present “substantial liabilities” to state services. To bring three kids to Ireland, a foreign worker has to prove a net income of nearly 37,000 euros. Yet the law still creates room for bureaucrats to deny a family's entry if they choose. If the aspiring sponsor's children are school-aged, for instance, the immigration service can deny them entry since their enrollment would burden the school system — even if the parent's income is above the required threshold.

WE'RE ASKING YOU

CHAPTER THREETHE LOSING GENERATION

A thousand miles south of Helsinki, in Rome, Italian families with money to spare benefit from a system which, since the 1970’s, has brought Filipino workers into their homes to clean houses, cook meals, and take care of Italian children. Today, that system has created in Italy one of the largest Filipino populations anywhere in the world. But in prioritizing labor, the Italian government and the employers it favors have neglected the children of those workers, who are typically treated as a burden on their parents’ working lives, and not as an asset in a country with a declining birthrate.

For immigrant workers in Italy, it’s important to keep the boss happy. Since Italian law only allows for employers — not spouses, brothers, sisters, aunts, or uncles — to sponsor a migrant worker’s residence permit, keeping a job is also essential to staying in the country.

But having a child can complicate the balance. While maternity leave is guaranteed under Italian law, domestic workers are explicitly denied the right because their first responsibility is to care for their clients’ families. If their kids are sick, migrant workers have to take time off work, but employers are often willing to fire their help for missing a day.

When Rowena Alota, a Filipino house cleaner in Rome, was forced to choose between her job and her daughter, Navie, she, like many Filipino parents in Italy, chose to send her daughter to the Philippines to be raised. Like many Filipino children, when Ronavie was old enough, her mother called her back to Rome to live with her. As Navie explains below, her life ever since has been marked by hardship.

Among young Filipinos in Rome, the sense of displacement that Navie describes is common. The thousands of Filipino children who arrive to Italy every year are not joining the Italian mainstream but forming their own society at its margins.

At night in Rome, Filipino youth caught between the country they left and the one they live in now will sometimes congregate around Piazza Vittorio to drink and smoke. Raphael, a 21-year-old Filipino, is one of those young people. Below, he explains some of what his life and the life of his peers is like.

In many European countries, young immigrants like the Filipinos who hang out on Piazza Vittorio are marginalized not just by the nature of their arrival. They’re also more likely to be poor than their native-born peers.

At 23 percent, the poverty rate for native children in Italy is high, but, at 31 percent, the rate for immigrant children is higher. As the above graphic shows, even some countries, like Belgium, which exhibit a relatively low poverty rate for native children, often see a significant proportion of immigrant children living in poverty. With their place in society characterized by such contrasts, is it any surprise that so many immigrant youth struggle to fit into their adopted societies?

WE’RE ASKING YOU

CHAPTER FOURLEFT BEHIND

When parents leave their home country for work, they often leave their children in the care of relatives. Sometimes, as in the case of Janet and her family, the arrangement is temporary. Once they've earned enough, parents can come home or bring their children to the new country. At other times, separation is permanent. Daily interactions between parents and children are mediated through technology. In some towns in the Philippines, like Alaminos, outside Metro Manila, most parents who could afford to go abroad for work already have.

Out of about 5,000 families in the Santa Rosa ward of the town of Alaminos, around 2,000 adults have left the Philippines to work, says a Lito Santos, a local councilmember. While families suffer from the absence of their members, he says it’s the ones who don’t have relatives abroad to send them money who struggle the most. As the map below shows, in some regions of the Philippines, one in every 25 people was working abroad in 2010, the most recent year for which statistics are available.

SOURCE: SURVEY ON OVERSEAS FILIPINO WORKERS (2010) OF THE NATIONAL STATISTICS OFFICE OF THE PHILIPPINES

For most of the workers we met, leaving home for a life abroad was the best of limited options. But whatever material advantages a parent’s job overseas may yield their children, the children still suffer from the separation when they are left behind, or social displacement in their new homes.

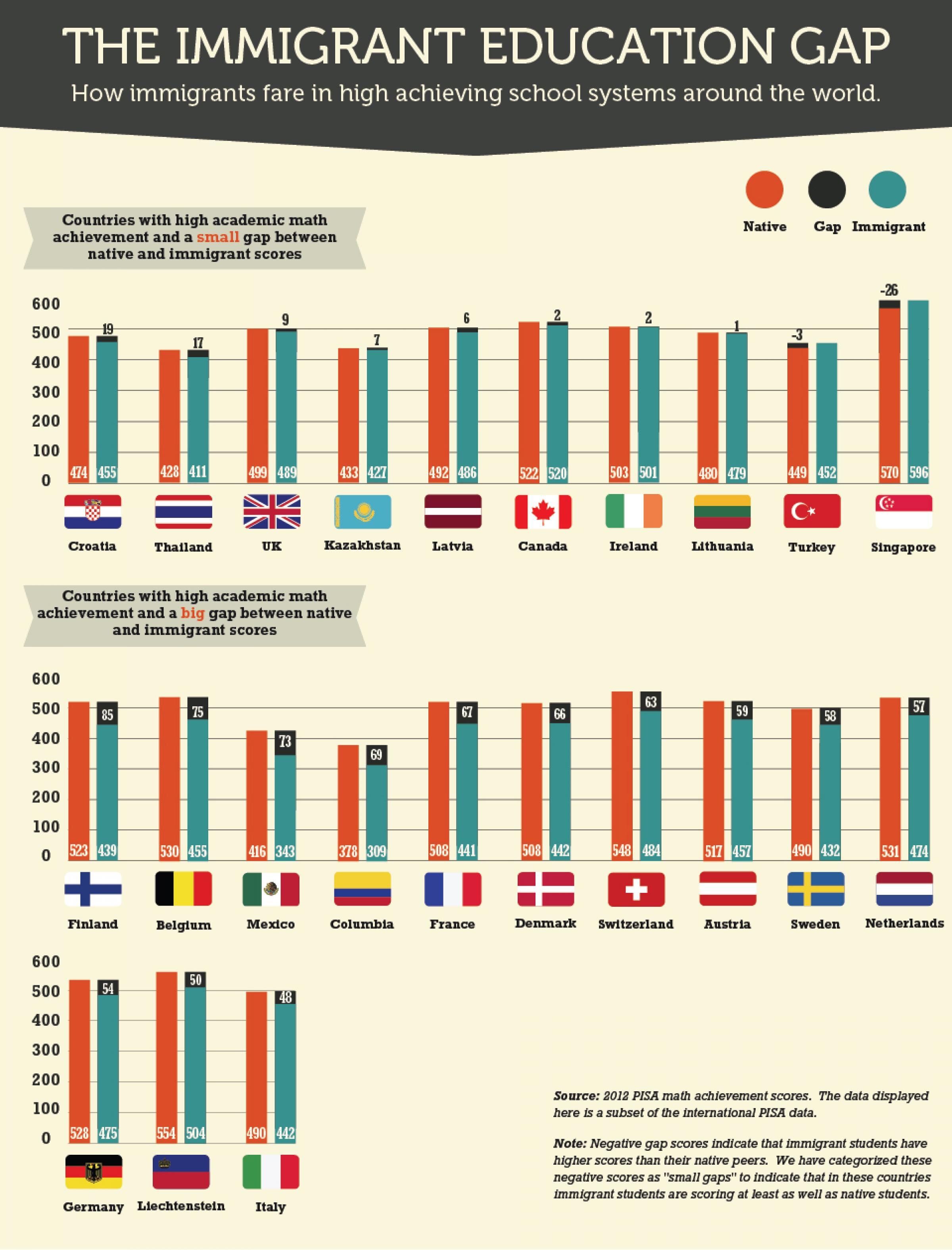

For destination countries, making immigrant children feel part of their new country will continue to be a major challenge. Schools can help integrate young immigrants. However, many countries that have achieved admirable results in educating native-born children have failed the immigrant students who come through the door. Finland is a prime example. In 2012, nonimmigrant students scored an average of 410 out of a possible 500 points on the OECD’s Program for International Student Assessment, a commonly accepted standardized test. But immigrant students in Finland averaged 85 points less. For these students, it’s as if the benefits of going to one of the strongest school systems in the world do not apply to them.

But other countries have succeeded in bringing a diverse body of students who perform equally well in school. About ten percent of all Canadian students were born outside the country. In some of the major metropolitan areas, the rate can exceed 25 percent. To ensure new students feel at ease in their new country, some school districts assess students’ academic needs before school starts. Parents who immigrate to Canada are often wealthy and well educated but, even when adjusting for language and income, immigrant students perform about as well as their nonimmigrant peers.

Helping immigrant children find a place in their new countries is not only a moral cause. If countries in Europe, North America, and East Asia are going to weather a future of declining birth rates, they need not just adult immigrants who are ready to work, but their children also. The first step is to see their potential, not only in unskilled jobs at the lowest levels of society, but at every level.

WE'RE ASKING YOU

CHECK OUT MORE STORIES ON THIS TOPIC

The #longread version of Excess Baggage