No Place Like Home

A Global Exploration of Violence Between Partners

An Investigative Report By: Lucian Perkins, Journalist, Email, Susana Seijas, Journalist, Email, Joanne Levine, Journalist, Email, and Pierre Kattar, Journalist, Email

CHAPTER 1

EVERYWHERE

A WOMAN IN HIDING AT A SHELTER IN MANAGUA, NICARAGUA.

In Sweden it’s 28 percent. In Nicaragua, 29. In Uganda it’s 59 percent.

Whether you call it “domestic violence”, “partner violence” or “intimate partner violence” there is one key reality: It’s everywhere. Every country and every culture. Every faith. Every education and economic level. Old and young. Men and women.

Of the 115 countries for which we aggregated the most recent data, the lowest prevalence rate is 5 percent. But 80 of these countries (just over two-thirds of them) have a rate at or above 20 percent. That means that, in many countries, at least one in five women have experienced violence at the hand of their partner.

Each individual experience of this violence is intensely personal. But when we pull back the lens and look at the bigger picture we can see how much we share across our national and cultural differences – whether it is from a personal story or how this violence affects society.

This is the story we want to share.

Our data team gathered and analyzed data on domestic violence from countries around the world and that data served as an informed source for our professional reporters. The most widely collected data focuses on women as victims of this violence in heterosexual relationships and hence our focus was similarly limited. For this project we defined domestic violence as physical and/or sexual violence between partners. Our journalists used this data and on the ground reporting to explore what we might learn by looking at this topic as a global, rather than local, issue.

The map below shows rates of domestic violence for 115 countries around the world. Angola, Bangladesh, and Kiribati are among those countries with the highest rates, while Armenia, Georgia, Morocco, and Switzerland join those with the lowest rates. Even accounting for limited data collection, we see all major religions, styles of government, economic conditions and a mosaic of cultural traditions and social norms. This isn’t about “them.” It’s about “us.”

TWENTY-NINE PERCENT OF WOMEN IN NICARAGUA HAVE EXPERIENCED DOMESTIC VIOLENCE.

CHAPTER TWO

THE PRICE

PRAYER SERVICE IN MASAYA, NICARAGUA, FOR TEACHER JOHANA GONZÁLEZ, 37, WHO WAS MURDERED BY HER EX-HUSBAND.

Domestic violence exacts costs that bleed from the individual into society.

Those costs may not be evident to all members of a community, but domestic violence burdens the justice and health systems. It also increases demand for social services including shelters and income support, causes lost productivity in the workplace and a resulting overall economic loss due to lost wages and taxes.

For people in violent relationships the costs are borne in very real and lasting emotional, psychological and physical ways. Some pay with their lives, as our team found in Nicaragua with the death of Johana González.

GRACIELA

Graciela’s story isn’t unique. Twenty-nine percent of Nicaraguan women have experienced domestic violence. In this particular way Nicaragua is not unusual. Its domestic violence rate is comparable with the United Kingdom, Barbados, Finland and New Zealand.

Abusers often physically and psychologically demean their partners, effectively diminishing their self-confidence. What many victims share – no matter their nationality, religion or socio-economic level — is a profound sense of isolation that emerges alongside a gradual increase in violence. This can be a dangerous combination: A lack of self-confidence, increasing violence and growing isolation often make it extremely difficult for victims to seek any type of help.

One victim told us, “I don’t want to say it’s like a drug or an addiction – but it’s hard to break free from the cycle. It’s conditioning, you know. You are being conditioned basically to believe that this is what you deserve, you don’t deserve more than this, you don’t even conceive what a normal relationship is because it’s what you … this is your daily reality.”

Graciela explains, “He would tell me, ‘You’re gonna die’ when he’d point the gun at me… I had many years like that with him. My daughter was born. Then he threatened to kill her if I didn’t keep living with him. He said he’d kill me and our daughter, and even kill my mom if I didn’t stay with him.”

SHELTER

A CHILDREN’S ROOM AT A DOMESTIC VIOLENCE SHELTER IN WESTERN SWEDEN.

ISOLATION

WIVECA HOLST, WHO WORKS AGAINST DOMESTIC VIOLENCE IN SWEDEN, KNOWS FIRST HAND.

SOCIETAL COSTS

Society. The community. The Family. The individual. No one is exempt. Everyone pays for this violence somehow.

Dr. Steven Lucas is a lead researcher on partner violence and health at the National Centre for Knowledge on Men’s Violence Against Women at Uppsala University in Sweden. His research indicates that the health of victims as a group is poorer, particularly in a “several-fold higher prevalence of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, but also psychosomatic symptoms.”

There are numerous health issues associated with domestic violence including stress, anxiety, diminished social function, alcohol or drug abuse, higher blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, sexual and reproductive health problems, miscarriage and premature births. According to a study published in June 2014 by The Lancet, partner violence is the leading cause of non-fatal injuries to women.

But communities also sustain the cost for domestic violence in myriad ways. It burdens the justice and health systems, increases demand for social services including shelters and income support, causes lost productivity in the workplace and a resulting overall economic loss due to lost wages and taxes.

DEATH

CHAPTER 3

THE LAW AND ATTITUDES

POLICE SUPERVISOR CHRISTINE ALALO BEGINS A 10-DAY CLASS FOR UGANDAN POLICE OFFICERS ON HOW TO DEAL WITH DOMESTIC VIOLENCE.

The law matters. Countries with laws that make beating, maiming or raping a spouse a crime have an average partner violence prevalence rate five percentage points lower than countries that do not have such laws.

THERE ARE QUITE A FEW COUNTER-EXAMPLES, HOWEVER. FOR EXAMPLE, UGANDA (59 PERCENT) PASSED A LAW CRIMINALIZING DOMESTIC VIOLENCE IN 2010, AND IT HAS A HIGHER THAN AVERAGE RATE OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE. THIS CHART ALLOWS US TO READILY SEE HIGH AND LOW INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE RATES AND THEIR CORRESPONDING LAW STATUS.

IN UGANDA, THE DOMESTIC VIOLENCE ACT WAS PASSED IN 2010 ONLY AFTER INTENSIVE GRASS ROOTS AND POLITICAL ADVOCACY CAMPAIGNS.

LAWS AREN'T EVERYTHING

Laws are important but they aren’t everything.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) issued a report in March 2013 indicating that in some developing countries attitudes and prevalence are connected. “The average prevalence of domestic violence in countries where there is a high acceptance of domestic violence is more than double the average of countries where there is a low acceptance of domestic violence. The relationship remains strong and significant even when taking into account the existence and quality of domestic violence laws and country income level, signaling that laws alone will not reduce violence against women.”

“IT’S A MAN’S PICTURE OF WHAT A WOMAN SHOULD BE AND HIS WISH TO CONTROL HER.” ANNA LENA MELLQUIST, DIRECTOR, OLIVIA SHELTER, SWEDEN.

ATTITUDES AND PREVALENCE

Our data and other studies show that countries where women are more accepting of domestic violence are also countries where more women are abused by their partners. The following graph shows this relationship for countries around the world. We can see that while there are broad global trends around the prevalence of intimate partner violence and social attitudes towards it, it’s also true that each country has a unique combination of elements that make for many exceptions to the trend.

CHAPTER 4

EVERYONE HAS A ROLE

ALAN HEISTERKAMP SPEAKING AT A VIOLENCE PREVENTION CONFERENCE IN STOCKHOLM: “WE ALSO NEED TO TAKE A 360 LOOK AT MALE CULTURE.”

Our cultural habits and social norms prescribe much of the way women and men interact. Understanding domestic violence requires exploring those norms and the social conditioning that forms them. So often, partner violence is seen through the prism of gender, and as a “women’s” issue.

That is not the case. Gender-based behavior is often taught and learned at a young age. Girls learn to be accommodating. Boys learn to be macho. Leveling the balance of power between the sexes must play a role.

We’ve looked at how important the attitude that women hold towards domestic violence is in a society. Let’s look a little more at men. Men as perpetrators. Men as victims. Men as agents of change in shifting our cultures.

VICTOR USED TO BEAT HIS WIFE. HE SAYS BY ATTENDING WORKSHOPS ON DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AND GETTING COUNSELING HE WAS ABLE TO CHANGE.

MEN CAN BE VICTIMS TOO

Victor’s story as an abuser is all too common. We tend to think of men as the perpetrators. What is lesser known — and lesser studied — is how men can be victims of partner violence. This phenomenon stays in the shadows, but the patterns, emotions and isolation are the same.

FOR THOSE WHO SURVIVE DOMESTIC VIOLENCE THE FEELINGS ARE UNIVERSAL. THIS IS ANTOINE’S EXPERIENCE.

SOCIAL NORMS

BREAKING THE SILENCE

Sweden is an interesting place to look at partner violence as it is widely lauded for its gender equality, which is demonstrated by the number of women who hold public office, serve as cabinet ministers, graduate from university and hold jobs. Family leave policies rank among the most progressive, including men as well as women, and the government provides excellent daycare centers. In fact, Sweden ranks fourth for gender parity according to the 2013 Global Gender Gap report published by the World Economic Forum. The same report places Nicaragua in 10th place on gender equality.

Despite its gender equality, a European Union study called, “Violence Against Women” puts Sweden’s domestic violence rate at 28 percent. While he was the Justice Minister of Sweden, Thomas Bodstroem declared, “Silence is a betrayal to all abused women, and a help to all violent men”.

Breaking the silence and making men part of the solution seem essential to diffusing the partner violence in our homes. Paul Bbuzibwa, an activist at the Center for Domestic Violence Prevention in Uganda sums it up well, “Men have more power to do whatever pleases them, even when it is at the expense of their partners. So, when you engage only ladies it is a disservice to them, because many of them can’t even start a discussion on violence against women. But when you involve men in a discussion they appreciate the discussion and some of them will start reflecting and engaging their colleagues.”

IT’S NOT A WOMENS’ ISSUE

ANNA LENA MELLQUIST WHO RUNS THE OLIVIA SHELTER IN WESTERN SWEDEN, TALKS ABOUT MEN AND POWER.

CHAPTER 5

NO SIMPLE SOLUTION

THE CENTER FOR DOMESTIC VIOLENCE PREVENTION IN KAMPALA, UGANDA, USES THEATER AND GAMES TO GET MEN AND WOMEN TALKING ABOUT HOW THEY USE POWER IN THEIR RELATIONSHIPS.

So, what’s being done to address this very specific and pernicious type of violence that unfolds in homes everywhere.

There’s no silver bullet, no single or simple solution for this complex social issue. On a global level our data analysis tells us that laws matter, social attitudes matter, gender equality and financial access matter. Our deeper data dive on Uganda may help us recognize the pathways forward.

UGANDA PASSED THE “DOMESTIC VIOLENCE ACT” IN 2010. BETWEEN 2000 AND 2011 THERE HAS BEEN A MEANINGFUL DECREASE IN THE NUMBER OF UGANDANS WHO FIND DOMESTIC VIOLENCE ACCEPTABLE. OUR GLOBAL DATA ASSESSMENT HAS INDICATED A LINK BETWEEN SOCIAL ATTITUDES TOWARDS PARTNER VIOLENCE AND PREVALENCE ON A COUNTRY LEVEL. WHAT STANDS OUT IN THIS CHART IS THAT IN SPITE OF THE CHANGES IN UGANDANS’ ATTITUDES THE PREVALENCE RATE OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE HAS REMAINED STEADY AT ABOUT 60 PERCENT.

CHANGING ATTITUDES

Those changes in attitudes come from a variety of places, but one sure place is the community outreach activists who inform the public about domestic violence, the law, their rights and ways to get help. They also spur conversation on partner violence in order to bring this topic from the shadows into the light.

AN ACTOR PLAYING THE HUSBAND FREEZES AS THE MODERATOR ASKS THE CROWD “DO YOU SEE VIOLENCE HAPPENING IN YOUR COMMUNITY?”

WHILE UGANDA’S NATIONAL PREVALENCE RATE OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE HASN’T MOVED MUCH BETWEEN 2006 AND 2011, IT IS INTERESTING TO NOTE THE DROP IN RATE OF REPORTED DOMESTIC VIOLENCE IN RURAL AREAS — FROM 62 PERCENT 2006 TO 52 PERCENT IN 2011. SOMETHING IS HAVING AN EFFECT.

Activists in Uganda, Nicaragua and many places in between use outreach, games and particularly theater to spark discussion and raise awareness of domestic violence.

MARIAM TORRES DIRECTS PLAYS ON DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AND IS DEVOTED TO MAKING A DIFFERENCE IN HER COMMUNITY.

POWER AND MONEY

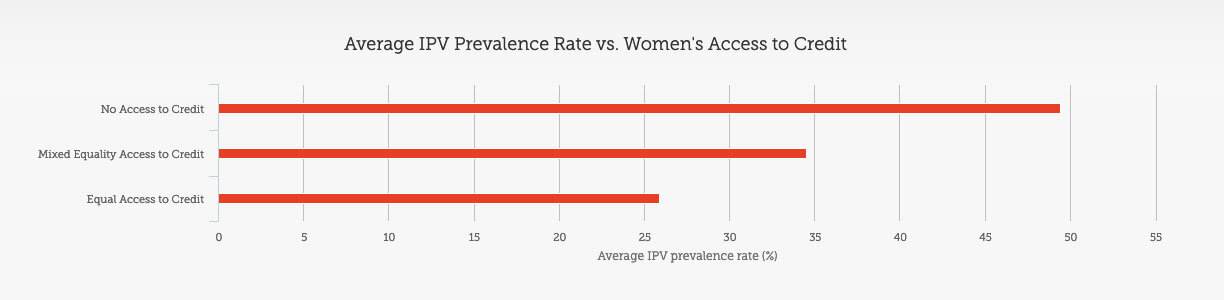

One of domestic violence’s many facets is the power dynamic between two people. That dynamic involves many things, but the social norms around gender equality – including financial equality – play a discernable role: Countries where women have more equal access to credit and the ability to own land have an average lower rate of domestic violence than those countries with weaker rights in these areas. In a related finding, the wealthiest Ugandan women are significantly less likely to report experiencing intimate partner violence than Uganda’s poorest women. (36% for the wealthiest compared to 60% for the poorest. Numbers from 2011.)

NANCY ABWOLA OF THE CENTER FOR DOMESTIC VIOLENCE PREVENTION DESCRIBES HOW HER ORGANIZATION CHALLENGES PEOPLE TO THINK DIFFERENTLY.

POWER. MONEY. LAND. THE THREE ARE DEEPLY INTERTWINED. CASE IN POINT: COUNTRIES WHERE WOMEN HAVE EQUAL ACCESS AS MEN TO AGRICULTURAL LAND OWNERSHIP HAVE LOWER RATES OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE. NICARAGUA IS DESCRIBED AS “WOMEN HAVE MIXED ACCESS TO LAND” AND UGANDA AS “WOMEN HAVE NO REAL ACCESS TO LAND.”

Grace Lwanga, who works at Kampala’s Center for Domestic Violence Prevention advises women to do something that’s unusual in Uganda: She recommends they own property in their name.

“Even working class women, when I talked to them you would find you have a job, you get your money, but when you are going to buy land the local leaders tell you, ‘No, it should be in the name of your husband.’ And tomorrow when you have a problem the title is not in your name.”

POWER. MONEY. WHEN WOMEN’S ACCESS TO CREDIT IS EQUAL TO MEN’S COUNTRIES HAVE LOWER PREVALENCE RATES OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE.

SHELTER

So many victims of domestic violence, regardless of their nationality or culture, share the core experience of profound isolation. Finding a safe place holds a meaningful key for women seeking solace from this abuse. These shelters can provide an understanding community, a place to sleep, food to eat as well as supplies and schooling for children.

Graciela, whose husband held a knife to their baby boy, is still in hiding at a shelter in Nicaragua. The shelter has been her lifeline, as similar shelters are for so many women across the globe.

Sometimes shelter isn’t a physical place, but a virtual one. That is the case at Stockholm’s Young Women’s Empowerment Center where girls reach out via the internet.

RAZOR WIRE SURROUNDS THE SHELTER WHERE GRACIELA STAYS.

STOCKHOLM’S YOUNG WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT CENTER RUNS AN ONLINE CHAT ROOM FOR YOUNG WOMEN EXPERIENCING VIOLENCE IN THEIR RELATIONSHIPS.

CHAPTER 6

MORE QUESTIONS

NICARAGUAN POLICE CAPTAIN NUBIA OCHOA IS A SUPPORTER OF 20-YEAR-OLD MARIAM TORRES’ DOMESTIC VIOLENCE ACTIVIST THEATER GROUP.

We know that physical and sexual violence between intimate partners is everywhere, not limited to any particular community. It occurs across the artificial boundaries we have built to differentiate ourselves: nationality, language, religion, culture, economic station or education level.

So, if this type of violence is so prevalent, why is it so invisible to the rest of us as we go about our daily lives? Why don’t we notice? And if we do notice, why don’t more of us speak up? What should we say when we do speak up?

These are hard questions.

There is no single or simple answer.

Our data analysis found that passing legislation, changing social attitudes towards domestic violence and improving gender equality are important factors in the discussion of domestic violence. Coupled with the opinions of the experts and others we spoke with, there is reason to believe that these things may even help prevent domestic violence from happening in the first place.

Once this type of abuse has begun, even if victims get out of an abusive relationship, it doesn’t guarantee a happy ending. Antoine divorced his abusive wife and plans to marry again. Graciela is in a shelter, struggling to build a new life. However, Johana divorced her abusive husband but he still hunted her down and killed her in front of a group of schoolchildren.

Women can’t fix this. Men can’t fix this. Only we, as members of our communities can collaboratively and collectively work in concert to diminish this prevalent, painful and costly societal challenge. If we don’t, what does it say about us?

MARYROSE TENTENA IS BEING HELPED BY ACTION AID IN UGANDA. “THIS IS WHERE I CAME AND THIS IS WHERE I HAVE FOUND PEACE.”