Generation Activist

Young People Choose Protest Over Traditional Politics

An Investigative Report By: Heather Krause, Chief Data Scientist, Email

THE DATA BEHIND THE STORY

Significant and surprising political shifts are in progress in many countries. Both the media and researchers have reported on filter bubbles, echo chambers, youth apathy and populism. That left us at Orb Media curious about how young people are thinking about government, politics and civic participation—and how current younger generations choose to act if they want to change something in their society.

Developing an understanding of how today’s youth (defined as people under 40) interact with their governments is complex and involves broad regional variability. Civic participation is linked to social, economic, and cultural environments, and around the world, these elements are constantly evolving. Technology has accelerated the rate of change over the past several decades, giving citizens new ways to connect with one another, and multiple, highly accessible platforms for discussion.

With differences from country to country, we sought to use data to view how young people participate in politics today, and determine if youth participation has changed over time.

Data analysis can provide valuable insights into trends, historical patterns, and emerging developments in the realm of civic engagement. Modern data science lets us examine specific conditions around the world for a more meaningful comparison. Social survey data collected over one or more decades can reveal trends over time and relationships between individual and global ideas—However, it cannot specifically pinpoint what is causing broad social trends.

Data Summary

Data was scientifically collected from 979,000 respondents from 128 countries. The data is included in nationally representative surveys.

Statistical analysis of data included rake weighting and multi-level linear models.

The data reveals a significant and growing generation gap between young adults and older people’s preferred means of participating in civil society.

Substantial generation gap among those declaring an interest in politics

Substantial youth voting power left on the table

Strong relationship between corruption and willingness to vote among younger adults.

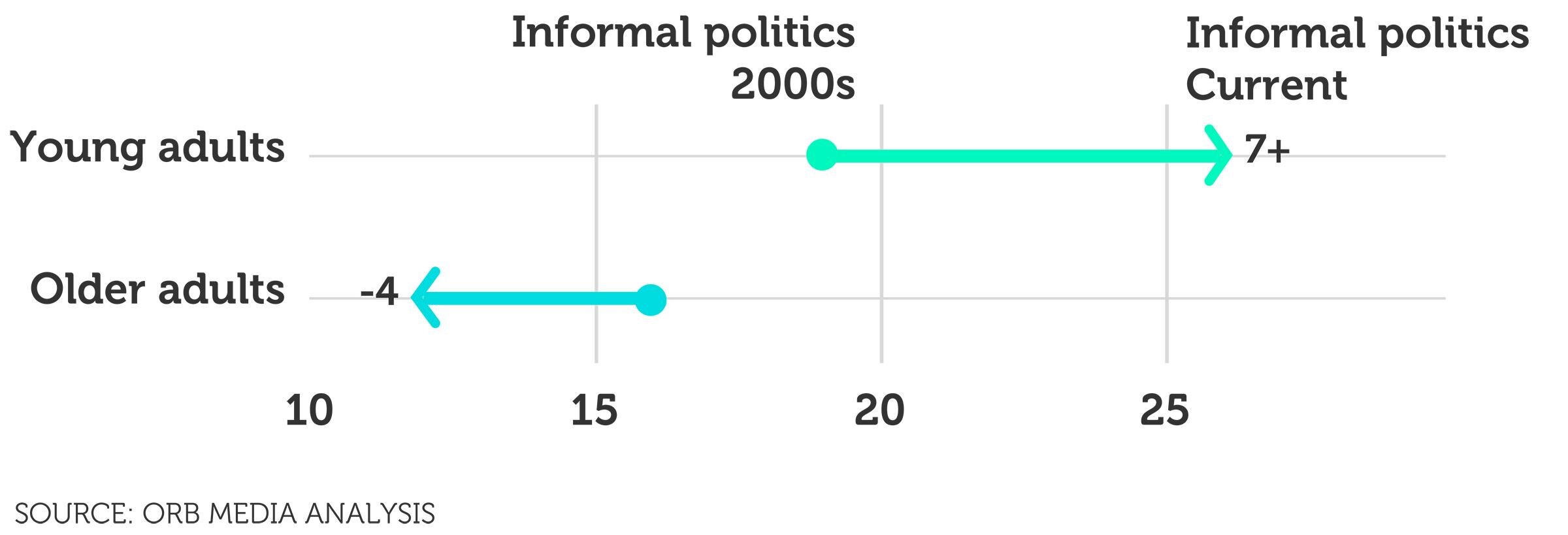

Orb Media’s data science team’s unique global analysis based on scientifically collected, nationally representative weighted data from 979,000 respondents in 128 countries found significant and meaningful upward trends in informal political activities such as protesting and demonstrating among younger adults, and found that older adults (over 40 years of age) are less likely to participate in these activities than they were several decades ago.

According to our analysis, in 2016 and 2017, a global generation gap of 6 to 13 percent emerged between people under 40 and those over 40 who reported participating in a demonstration or protest.

We then analyzed the political activities of those respondents who said they were interested in politics. Over half the respondents indicated that they were interested in politics. According to our data, the relative proportion of young and older people reporting political interest has remained steady within our data.

According to the data, adults younger than 40 are between nine and 17 percent more likely to prefer informal political activity than those older than 40—a significant increase from the early 2000s, when the younger group was only three percent more likely to protest. This trend is a global phenomenon and appears to be growing.

We have also found that informal political activities such as protesting and demonstrating are not always accompanied by young people actually voting. Our data shows a relationship between an individual’s perception of corruption and their likelihood to vote. This relationship is much stronger for voters under 40 than for voters over 40.

Our Data Collection Methods

Large, scientifically-collected social data can help illustrate how young people across the globe participate in the government and politics of their country. The value of these large global datasets is that they can transcend partisan perspectives and narrow national focuses.

Orb Media also used its unique Listen and Learn toolkit to collect data in several different ways and examined it using modern, robust statistical analysis. This enabled us to explore global trends, compare countries and age groups, and analyze the different factors at play.

We worked with data owners to access the raw data behind dozens of large, scientifically-collected datasets. These included the European Social Survey (2002-2016), the Caucasus Barometer (2008-2017), The Americas Barometer (2004-2017), the Asian Barometer (2000-2016), the Afro Barometer (2001-2016), The World Values Survey (1984-2014), the Eurobarometer (selected years 1980-2017), the USA’s General Social Survey (1980-2016), Canada’s General Social Survey (1985-2015).

These datasets are collected using national probability samples that give every citizen in each country an equal chance of being selected to participate in the survey. Whether using census household lists or a multistage area approach, the method for selecting sampling units is always randomized. The samples may be stratified or weighted to ensure adequate and correct coverage of rural areas and minority populations.

The data is collected using professionally trained enumerators. Quality checks are enforced at every stage of data conversion to ensure that information from paper returns is edited, coded, and entered correctly for purposes of computer analysis.

Orb Media obtained access to the record level data, meaning that we had access to the full individual level data points, including a selection of survey sample weights.

The data collected for these surveys uses a standard questionnaire instrument containing a core module of identical or functionally equivalent questions. Wherever possible, theoretical concepts are measured with multiple items in order to enable testing for construct validity. The wording of items is determined by balancing various criteria, including: the research themes emphasized in the survey, the comprehensibility of the item to lay respondents, and the proven effectiveness of the item when tested in previous surveys.

These datasets were merged using stratified survey sample weights and rake weighting—a method of merging data that helps to correct for differences in survey methodology and eliminates deviations between the sample and the reference population which could skew results. The final sample included 979,169 respondents from 128 countries. We then used hierarchical linear modeling to estimate trends and effects over time. We used Wald tests to assess statistical significance. We used Bonferroni adjustments for the multiple models.

In order to supplement the large global database and encourage audience participation in the story, a survey was designed by Orb to collect real-time data. The survey includes six questions that are either exact replicas of the questions asked in the large global surveys or closely adapted versions. This survey was circulated online to collect a convenience sample of data. The survey was also used in a few select countries by paid professional enumerators to collect more up-to-date accurate in-country data. At the time of writing, the 2018 data included 3,754 respondents from 52 countries.

The indicators that were selected to measure our concepts were:

Age: Self-reported year of birth

Informal political activities: Participation in protest and/or demonstration

Formal political activities: Participation in campaigning or other organized activities as part of a political party

Political interest: Self-report of level of political interest

Voting: Self-report of voting behavior

Perception of corruption: Self-reported perception of corruption and/or level of trust in respondent’s country’s government

The strengths of this analysis exist in the multiyear and multicountry datasets of scientifically collected data and allow for robust comparison of nuanced trends over time both within and between countries. The use of advanced statistical methods allows us to estimate what trends are most likely to be meaningful and which are more likely to simply be noise.

The limitations of the analysis lay largely in the fact that the social survey data is all self-reporting. This means that our findings are subject to sources of error injected by respondents stretching the truth and the respondents’ variable interpretation of the wording of each question.

Findings

Participation in Political Activities

As we analyzed the data, one trend emerged almost immediately—a shift in the way that young people choose to participate in civic society.

In the most recent years, about 26 percent of politically involved young people chose to get involved through protests. At the same time, about 12 percent of politically involved older people chose to get involved through protests. This is a significant increase from the early 2000s, when under-40s were only three percent more likely to protest.

THE AGE PARTICIPATION GAP IN INFORMAL POLITICAL ACTIVITIES HAS INCREASED OVER TIME

Percentages for politically interest people

Young citizens are becoming increasingly more likely to participate in informal political activities (protests and demonstrations) than their older counterparts. Worldwide, politically interested young people are currently 9 to 17 percent more likely to be involved in these informal activities.

THE AGE PARTICIPATION GAP IN INFORMAL POLITICAL ACTIVITIES EXISTS IN MOST COUNTRIES

Percentages for politically interest people

Of course, both these numbers vary significantly from country to country. Some of the countries with the largest current gaps include Austria, Bulgaria, Slovenia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Columbia, and Poland.

Here is the complete table of current individual country generation gaps. The global margin of error is 4.75 percent.

THE AGE PARTICIPATION GAP IN FORMAL POLITICAL ACTIVITIES EXISTS IN MOST COUNTRIES

Percentages for politically interest people

The association between the younger cohort’s likelihood to participate in informal political activities and its likelihood to vote is decreasing. In other words, in the past, if a young person was interested in politics and involved in protest, they were also more likely to vote. In the most recent year, however, this is not the case. In the 2000s, 15 percent of the young population both voted and participated in protests, but this number fell to 7 percent in 2017.

Voting Behavior

When we compare the percentage of eligible voters under 40 to the percentage of people in that group who say they voted, and to the same numbers among people over 40, it becomes clear that in some countries, a significant amount of voting power is “left on the table.” Globally, 4-11 percent (8 percent on average) of youth voting power is not exercised, though there is variation between countries. Young people do not make up the same proportion of people who voted that they make up within the proportion of eligible voters. In some places, such as Poland, Iceland, Sudan, and Costa Rica, nearly all eligible young voters vote. The details of this calculation are in the endnote below [i].

YOUNG PEOPLE LEAVE SOME OF THEIR VOTING POWER ON THE TABLE

Here is the complete table:

Difference in percent of eligible voters under 40 and the percent of actual voters under 40. Margin of error for individual countries can be requested. The global margin of error is 6 percent.

These numbers are often striking. Here are some countries that see much lower voting rates among youth:

Zimbabwe (2016): While a full 38 percent of Zimbabwe’s eligible electorate is young, only 33 percent of votes are cast by young people.

USA: 22 percent of eligible voters are young, but young people make up only 15 percent of actual voters.

Jamaica: Jamaican voters display the same gap, as 28 percent of eligible voters are young, and only 21 percent of actual voters are young.

So why are young voters in some areas of the world voting less often? What factors influence their decision?

We looked at economics and unemployment rates, immigration, perceptions about immigration, and general interest in politics—None of these seemed to have any meaningful or measurable relationship to voting behavior.

However, one variable—corruption—was strongly related to voting behavior in young people, much more so than in older people.

Perceptions About Corruption: Correlation or Causation?

We wondered if individual citizen’s perceptions generally aligned with experts’ opinions on the level of corruption in each country. We analyzed the citizen level of perceived corruption with the expert opinions from Transparency International’s Corruption Index, and the results are closely related. In general, the countries that citizens view as most corrupt are generally the same countries indicated by external experts.

Additionally, perceptions about corruption among the younger and older segments of the population were very similar. The key difference was in whether those beliefs influenced an individual’s decision about whether to vote.

We found that in individuals under 40, perception of corruption and voting behavior is so strongly linked that the relationship could be considered causal. Among older individuals, the relationship is not as strong. Young people seem to be making voting behavior decisions related to their perception of corruption in their government.

THE PERCEPTION OF CORRUPTION IS RELATED TO VOTING BEHAVIOUR OF YOUNG PEOPLE

We employed propensity score matching, which is a method of conducting causal analysis in the absence of experimental data. The results of this analysis were statistically significant and strengthened the case for causality.

The essential takeaway is this: If a young person believes their government to be corrupt, they are less likely to vote.

On a global level, people under 40 who believe their government is corrupt are 7-15 percent less likely to vote than those of the same age group who believe their government is not corrupt.

THE PERCEPTION OF CORRUPTION IS RELATED TO VOTING BEHAVIOUR OF YOUNG PEOPLE

Top 25 countries

Those over 40 who believe their government is corrupt are only 4-7 percent less likely to vote than those who believe their government is not corrupt.

THERE IS AN AGE GAP IN THE RELATIONSHIP OF PERCEPTION OF VOTING BEHAVIOUR

The countries where the most recent data indicated that perception of corruption had the most impact on young eligible voters’ decision to exercise their voting rights included Sudan (52%), Morocco (48%), and the Netherlands (37%). A more moderate percentage (20-22%) of young voters in Poland and Zimbabwe reported that corruption impacted their voting decision. In some countries like the USA and India, only a small percentage (2 to 4%) of young voters indicated corruption as a significant factor in their likelihood to vote. In other countries, such as Belgium, Colombia, Haiti, Iceland, Ireland, Mali, Mexico, and Nigeria, there was no significant relationship between the individual’s perception of corruption and their likelihood to vote.

Here is the complete table of the level of relationship on perception of corruption to probability of voting in people under 40. The global margin of error is 5 percent.

The 2017 Corruption Perceptions Index ranks 180 countries around the world by perceived levels of public sector corruption according to experts and businesspeople. Remarkably, there was no direct association between countries’ ranking on the Corruption Index and the level of impact on voting behavior. Countries with all levels of corruption experience varying impacts of related perceptions on the likelihood of young people to vote.

In other words, it is possible for a young person in a less corrupt country to be less likely to vote if they find their government to be corrupt than a young person in a more corrupt country. This points to the possibility of becoming accustomed to corruption as a normal way of being so that it doesn’t impact a citizen’s behavior.

In Sudan, for example, the perception of corruption has a significant impact (52%) on young voters’ likelihood to vote. Sudan is very low on the global Corruption Index ranking, at 175 out of 180. In the Netherlands, on the other hand, the perception of corruption also has a significant impact (37%) on the youth’s likelihood to vote, yet the country is much higher on the global ranking of corruption (8 out of 180). Morocco ranks in the middle of the Index, at 81 out of 180, yet reports the second-highest rate of impact (48%).

In summary, our data analysis has revealed that people under 40 are significantly more likely to be involved in informal types of political activities such as protesting and demonstrating than people over 40. This is a global phenomenon and appears to be growing over time. We have also found that these informal political actions are not always accompanied by young people actually voting. Our data also shows a relationship between an individual’s perception of corruption and their likelihood to vote. This relationship is much stronger for voters under 40 than for voters over 40.

[i] Calculation #1: Count of total eligible voter population that is young DIVIDED BY (Count of total eligible voter population that is young + Count of total eligible voter population that is old). This gives us a proportion of potential voting power available to young people.

Calculation #2: Count of total actual voter population that is young DIVIDED BY (Count of total actual voter population that is young + Count of total actual voter population that is old). This gives us a proportion of actual voting power used by young people.

Calculation #1 MINUS Calculation #2 gives us the amount of voting power young people left on the table. For example, in France, Calculation #1 gives us 20% (meaning that 20% of the potential vote in France goes to young people). Calculation #2 gives us 13% (meaning that 13% of the actual vote went to young people). Twenty percent minus 13% gives us 7% (meaning that young people in France left 7% of their voting power on the table).