At 85, Claude Copin, a retired French welder, may have discovered a secret to living a long, healthy life. She stays active by playing a pétanque game with friends in a Paris park. And she has made friends with her teammates’ children, many of whom are teenagers. They take her to parties and movies—sometimes forgetting that she might need a rest before they do.

“I make my life beautiful,” says Copin. “I am still healthy because I have activities and I meet people.”

Copin is right. A growing body of scientific research and global data collected and analyzed by Orb Media shows a strong connection between how we view old age and how well we age. Individuals with a positive attitude towards old age are likely to live longer and in better health than those with a negative attitude. And those with a negative view of aging are more likely to suffer a heart attack, a stroke or die several years sooner. Older people in countries with low levels of respect for the elderly are at risk for worse mental and physical health and higher levels of poverty. A simple shift in attitude, the research shows, could improve a lot.

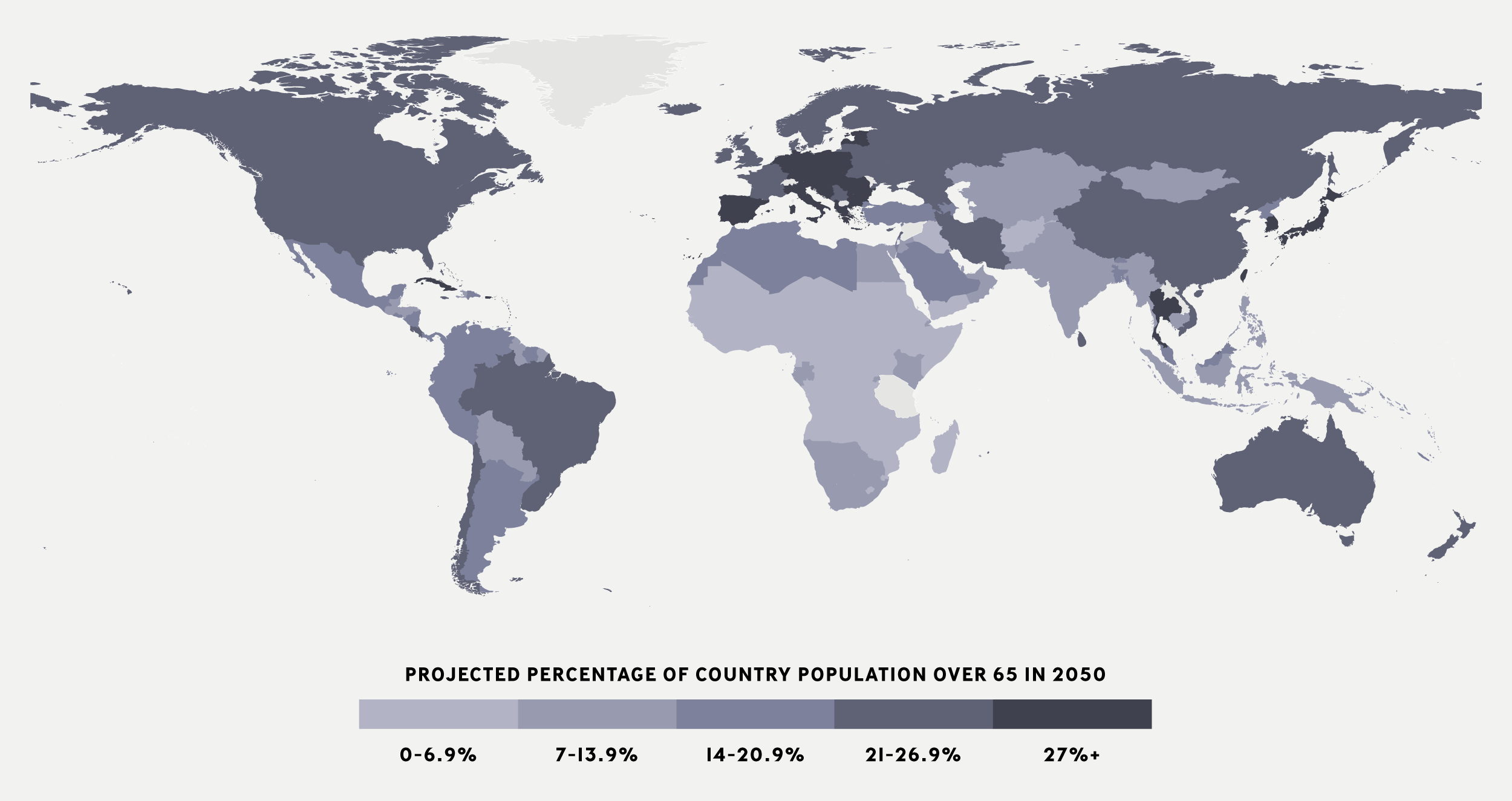

Healthy aging is increasingly important: Countries everywhere outside of Africa are rapidly growing older. If population trends continue, by 2050 nearly one out of six people in the world will be over 65, and close to half a billion will be older than 80.

A World of Experienced People

Today the elderly are 8.3% of the world’s population. In 2050 they will be 15.8%.

“Old age is actually an achievement,” says Marília Viana Berzins, a Brazilian social worker and advocate for the elderly. “It’s humanity’s biggest achievement of the last century.”

Yet, in many countries, the public debate about this massive demographic shift is often focused on the anticipated economic and social challenges of caregiving and health care. In a world brimming with older people, negative views of old age are surprisingly common.

A World Health Organization analysis found that 60 percent of people surveyed across 57 countries reported low levels of respect for older people. The elderly are often viewed as less competent and less able than younger people. They are considered a burden on society and their families, rather than being recognized for their valuable knowledge, wisdom and experience.

LEARN WHY AN EXTENDED BRAZILIAN FAMILY APPRECIATES THE ELDERLY.

Globally, age discrimination is more common than sexism and racism, says Alana Officer, a Senior Health Adviser with the World Health Organization’s Department of Ageing and Life Course. For people over 65, that can result in job or housing discrimination, loss of income or isolation.

Orb Media compiled data from 150,000 people in 101 countries to learn about their levels of respect for older people. The data show the level of respect varies significantly from country to country. Pakistan was among the countries that scored the highest.

“Countries with higher levels of respect for the elderly report lower rates of relative poverty for people over 50.”

Respect for older people is a long-standing tradition in Pakistan, says Faiza Mushtaq, an assistant professor of sociology at the Institute of Business Administration in Karachi, Pakistan. Typically, older people there have been cared for in the family and are considered the head of the household, often making all decisions late into old age. But as greater numbers of young people move to cities, traditional family structures are being disrupted, making it harder to care for elders. Without a government safety net, many older people fall into severe poverty, she says.

Nonetheless, there are tangible benefits to the way elders are viewed in Pakistan, says Mushtaq. “This attitude towards aging is a much healthier embrace of the aging process, rather than having all of your notions of well-being and attractiveness and self-worth being tied so closely to youth,” she says.

Variation of Respect Towards the Elderly

Japan, with the world’s longest lifespans and low birth rates, is at the leading edge of this global demographic shift. There, Orb found low levels of respect for the elderly. Dr. Kozo Ishitobi, who, at 82, continues to work as a physician at a nursing home, says that older people were traditionally seen as a burden. “Japanese people are starting to realize that elderly people need support,” he says. “We all go through it, so we should support each other.”

While most people are retired long before they reach their 80s, Dr. Ishitobi has dedicated his own later years to helping other older people. “We can’t keep our youthful faces forever. I was once a handsome guy, but I have gotten more wrinkles,” he laughs.

It turns out that respect and other attitudes towards aging have broad implications for us as individuals. Becca Levy, a professor of epidemiology at the Yale School of Public Health in the United States, has been fascinated by the power of age stereotypes for decades and is the leading researcher in the field. She started her work in the 1990s with a hunch. If older people are respected in society, perhaps that improves their self-image. “That may in turn actually influence their physiology and that may influence their health,” says Levy.

Over the last two and a half decades, Levy and the researchers that followed have found just that: Those with positive views about old age live longer and age better. They are less likely to be depressed or anxious, and they show increased well-being and recover more quickly from disability. They also are less likely to develop dementia and the markers of Alzheimer’s disease—devastating conditions that will only become more widespread as people in more countries live longer.

DISCOVER WHY POSITIVE VIEWS OF AGING CAN EXTEND LIFE.

In one study, Levy found that Americans with more positive views on aging who were tracked over decades lived 7.5 years longer than those with negative views. Studies in Germany and Australia have found similar results. “Some of the magnitudes of the findings have been surprising,” says Levy.

The power of age stereotypes is even evident deep in human biology. One recent study found that the cells of those who have more positive views of the elderly actually aged more slowly than those who had negative views.

Orb’s research and analysis found that these effects can also be seen across cultures. Older people in countries with high levels of respect for the elderly report better mental and physical health compared to others in their country, according to data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the United Nations and others. Those countries also report lower rates of poverty among people over 50 compared to younger people in each country.

It seems too simple: How can holding a better attitude towards old age help someone live longer? Levy found that people with negative views of old age have higher levels of stress. And stress has been correlated with a range of health problems. Those who expect a better life in old age have been shown to be more likely to exercise, eat a balanced diet and visit the doctor, says Levy.

That has been the case for 57-year-old Marta Nazaré Balbino Prates, who moved her family into her parents’ home in São Paulo, Brazil a decade ago. She had to quit her job as a nutritionist at a hospital to care for her parents (her father passed away at the beginning of the year.) It has been hard financially and emotionally. But, she says, the experience has made her think about the kind of life she wants when she is older. “I try to watch what I eat. I work out as much as possible,” she says, “so I can reach old age in good physical condition.”

We should be grateful that we are even concerned about growing old, says Berzins, the Brazilian social worker who founded Observatory of Human Longevity and Aging, which trains care workers and advocates for the elderly. But in Brazil, Berzins says, old age has become associated with incapacity. “When we change this mindset and old age is seen like just a stage of life, we’ll move forward,” she says. “And the elderly will be treated with more respect.”

Shifting stereotypes is no simple feat. People develop their views on aging when they are toddlers, says Corinna Loeckenhoff, an associate professor of gerontology in medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, who has studied age stereotypes across cultures. But these views also change based on experience. Unfortunately, negative beliefs are often built on inaccurate impressions.

“People keep mixing up aging and dying.”

As people grow older, their health usually remains stable until about five years before they die, says Loeckenhoff. Only then will most people experience the mental and physical decline most associated with old age. “People keep mixing up aging and dying,” she says.

Some research shows that increasing meaningful contact between younger and older people can break down negative stereotypes. Samina Vertejee, a 50-year-old assistant professor at the Aga Khan University School of Nursing and Midwifery in Karachi, Pakistan, lives with her 86-year-old mother, Sherbanoo Vertejee, and her brother, sister-in-law and their two children. “My mother is everything in the family,” Vertejee says. “By virtue of our culture, religion and strong family system, my mother has a strong place in the family.”

Vertejee’s sister-in-law, Mehrunnisa Iqbal Vertejee, cares for Sherbanoo most of the time, something that she says is important so her children can see how older people should be treated. Despite Sherbanoo’s limited mobility, she appreciates the care she receives. “My family tries their level best to keep me comfortable and happy, which is a source of joy for me in this old age,” Sherbanoo says.

The experience of living in a multi-generational household, along with growing up in a culture that respects older people, has left Vertejee with a very positive view of old age. “Old age is not a matter of fear, but a matter of cherishing,” she says. “I will be really enjoying life in old age.”

AGING OPPOSITES: PAKISTAN RESPECTS OLDER PEOPLE MORE THAN JAPAN.

But what about people in countries where the elderly are not respected? Levy, who pioneered the research on age stereotypes, says that despite cultural messages, people can determine for themselves how they think about aging. Those who watch less TV, participate less in social media, and have more resistant personalities are more likely to hold more positive views of aging, Levy says.

That has certainly been the case for Dr. Ishitobi in Japan. Over the last 13 years, he has rejected the medical norms for how to treat people nearing death and has worked to find a better way to care for them. He is used to challenging accepted ways of thinking. And his views of aging are no different. He has been able to find happiness and meaning in his own later years, even in a country where negative views of old age are still common.

“When you get older, you focus more on how you can be of value to society. This is what makes us human,” he says. “It’s okay to age. Enjoy aging, I say. Just a slight change in mindset will result in big differences.”