Inside a busy roadside restaurant in the Central Java town of Solo in Indonesia, Joko Tri Harmanto scooped strips of breaded tempeh from oil sizzling in a blackened wok early on a recent Saturday morning. Next to him, a friend poured cups of steaming broth over bowls of rice to make a soup called sotos. Customers stood at the entry to the kitchen placing orders as the pair worked to keep up with the breakfast rush.

Harmanto and his friend, Wasiran, live a few houses away from each other just around the corner. But they are not just friends or business partners. Harmanto opened this restaurant with Wasiran because of one powerful concern: that Wasiran might join a violent group. “He is less fortunate economically, so I grabbed him so he won’t take part,” says Harmanto.

Harmanto says he knew that Wasiran was at risk the way a soccer coach can spot a promising player: Experience. Harmanto is a former terrorist himself, with the blood of hundreds on his hands. In 2002, Harmanto helped build the massive car bomb that the Al Qaeda-affiliated group, Jemaah Islamiyah, blew up in Bali. It killed 202 people. Hundreds more were injured, and Bali’s tourist economy suffered for years.

Now, he is trying to prevent others from following his path toward violence — starting with his friend.

JOKO TRI HARMANTO HELPED BUILD THE BOMB THAT KILLED 202 PEOPLE IN BALI IN 2002. HE HAS SINCE REJECTED VIOLENCE, EXCEPT IN SELF-DEFENSE. TODAY, HE HELPS DETER OTHERS, INCLUDING HIS NEIGHBOR, WASIRAN, FROM JOINING VIOLENT GROUPS. (ANDREAS VINGAARD FOR ORB MEDIA)

Wasiran is no outlier. Orb Media's reporting and data analysis shows that terrorism has been spreading to more countries, and that the acceptance of violence against civilians is growing in nearly every region of the world. Despite trillions of dollars spent on fighting terrorism since the attacks on September 11, 2001, more countries than ever are experiencing terrorism.(1)

At the same time, efforts to prevent terrorist recruitment have been slow to materialize and are localized, rarely based on the best research and lack rigorous evaluation.(2,3,4) Despite all of the global focus on protecting citizens from violent attacks and killing and arresting terrorists, governments have paid little attention to the pipeline of those joining the terrorist ranks.

“We are not doing enough on prevention,” says Eric Rosand, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington, DC, who directs The Prevention Project: Organizing Against Violent Extremism. “We have just been doing more of the same and more of it.”

In fact, there is little agreement on just how to prevent people from getting recruited. Academics have a basic understanding of why people join these groups, but the research is limited and not well funded. And there is little evidence to indicate which approaches work best.

Harmanto has his own deeply personal approach to prevention based on his experience and ideology that he relates to student and religious groups. So far it has also worked for his friend Wasiran. “I used to be chaotic, I was ignorant, I didn’t care about others,” says Wasiran, aware that he was a prime target for recruitment in Solo, a city that has a history of violent extremism. “After I learned from him, thank God, I was able to control my emotions.”

He, like Harmanto, retains a hard-line view of Islam and believes his religion is under attack in Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim-majority country. Yet now, he believes that violence should only be used in self-defense. “After I met him, I learned a lot about religion, how to live in society,” Wasiran says.

But that idea — that one can curb the impulse to violence while leaving radical ideology unchanged — is controversial. In fact, it is the opposite of the approach taken by programs in Germany that date back to the 1980s.

“Right-wing extremism that isn’t even violent, that is really alarming to us,” says Claudia Dantschke, project director with Hayat-Germany in Berlin, which works with the families of young people who are being radicalized. Because the country’s former Nazi ideology resulted in genocide and world war, extremist ideology is not tolerated in Germany.

“The ideology justifies the use of violence,” says Dantschke. “It tells you who you are allowed to kill and when you are allowed to kill. Ideology is the core of the violence.”

It may be that these opposing approaches work well in their own countries. Or that it is pointless to change ideology, as some say in Indonesia, or that leaving the ideology alone simply allows people to turn back toward violence. No one knows for sure because, as countries experiment with different approaches, there is little data available on the outcomes.

“You are not going to be able to make definitive judgments on which programs work,” says JD Maddox, an adjunct professor of national securities studies at George Mason University and a former counterterrorism official in several US government agencies. In part because political priorities shift over time resulting in a lack of data or a clear strategy, efforts to curb recruitment taking place around the world may never result in widespread, effective programs. “This will be a problem for a long time to come,” he says.

CLAUDIA DANTSCHKE WORKS WITH HAYAT-GERMANY, WHERE SHE COUNSELS FAMILIES OF YOUNG PEOPLE AT RISK OF RADICALIZATION. SHE SAYS THAT IDEOLOGY MUST BE CHANGED. IT IS AT THE ROOT OF EXTREMIST VIOLENCE. (CHRISTOPH KUBE FOR ORB MEDIA)

For most people, the idea of becoming a terrorist is unimaginable. Deciding that it is okay to kill others for a political or religious goal is illegal and considered immoral by most, and breaks many cultural and religious taboos. And yet its acceptability is growing around the world among a small percentage of people just as terrorism is spreading even further.

When it comes to fighting terrorism, governments have spent money on nearly everything except preventing people from joining these groups in the first place. According to a recent report from the Stimson Center, a nonpartisan policy research organization, the US government alone spent $2.8 trillion fighting terrorism between 2002 and 2016.(5) Of that, only $11 billion — less than half of one percent of the total — was spent on foreign aid for counterterrorism measures outside of war zones. That includes everything from countering terrorist messaging to training police and providing grants for weapons purchases. Only a small percentage of that money was spent on prevention programs.

That is a problem, says Rosand. ISIS has recruited from over 100 countries. The number of countries experiencing terrorist attacks has been rising since 2004 according to Orb’s analysis of the Global Terrorism Database, the most widely used measure of terrorist activity. Because terrorist attacks are rare and can vary year to year, Orb used a moving average--the average number of countries with attacks in the five previous years for each year between 2000 and 2017. Over 100 countries experienced attacks in 2016 and 2017 — more than any year this century.(6)

“There is no evidence that any of this reduces the terrorist threat in the long term,” says Rosand of the militarized approach governments have taken. In fact, he says drone strikes and other uses of the military can radicalize a population, leading to even further recruitment. “More countries are affected by terrorism than ever before.”

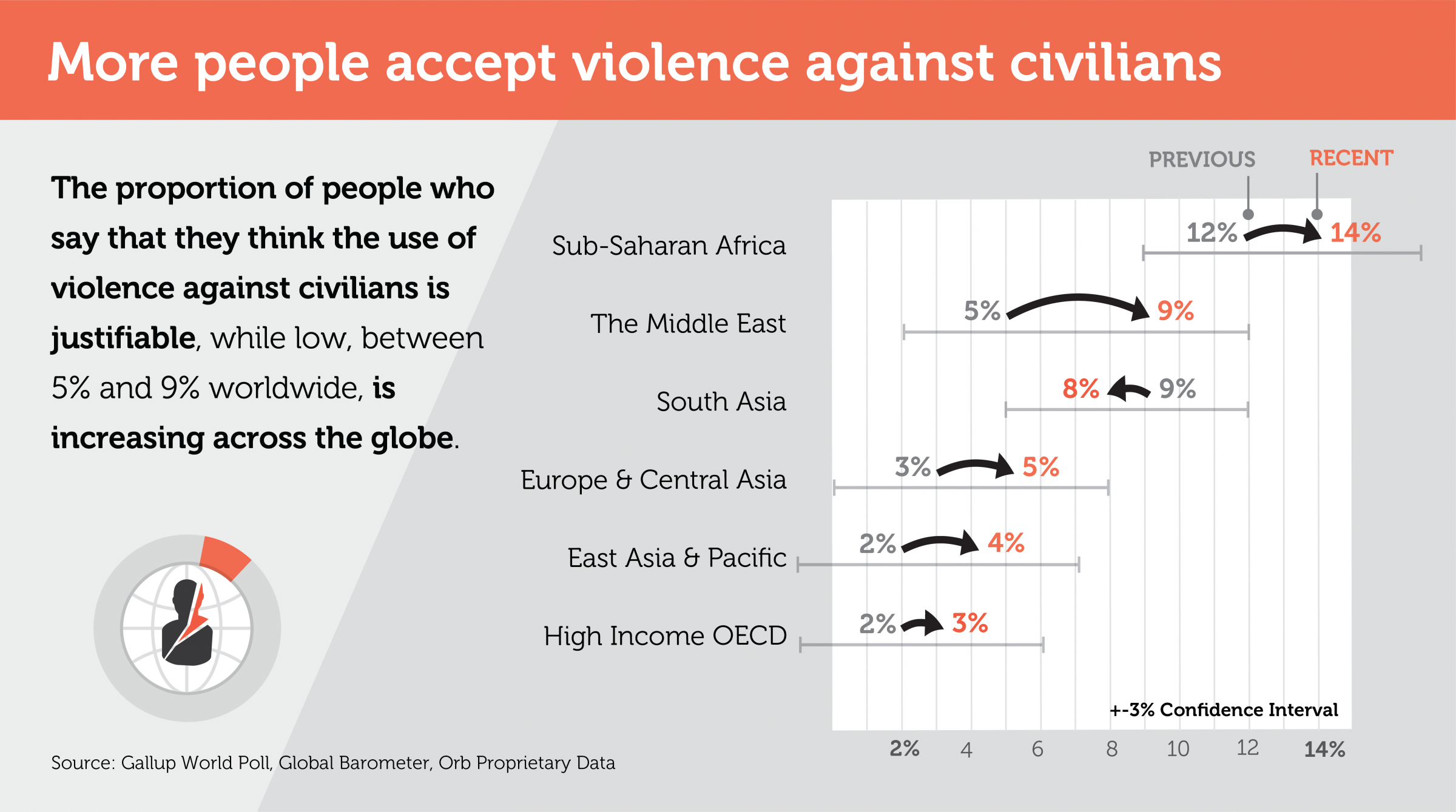

Orb Media analysis of polling data from 64 countries estimates that a growing number of people in nearly every region of the world find it completely acceptable for non-state groups to use violence toward civilians. Previously, this question has been used in academic research to analyze support for extremist violence. Acceptance doubled in East Asia and the Pacific, jumping from two percent to four percent in the years between the two periods the researchers measured: 2002-2009 and 2012-2018. In the Middle East, support jumped from five percent to nine percent. High-income OECD countries (34 countries made up mostly of those in Europe) saw support rise from two percent to three percent. Sub-Saharan Africa had the highest acceptance of terrorism: There, support grew from 12 percent to 14 percent.

While experts say that one can’t draw a direct line between these attitudes and terrorist recruitment, Clark McCauley, a professor emeritus of psychology at Bryn Mawr College who has studied terrorism for decades, says that some people who feel this way may be more open to terrorist groups. “Yes, it does make sense if people are open to political violence,” he says.

Globally, there is no agreed-upon definition of terrorism, and the label can be used either to accurately describe a group or to tar and marginalize legitimate dissenters. In this article, Orb Media is using the definition of terrorism created by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), a group of academic researchers and independent experts who maintain the Global Terrorism Database. It is the threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by a non-state actor to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation. (7)

By that definition, terrorism has been used by groups with just about every ideology and religion for over a century, says John Horgan, a professor in the Global Studies Institute and the psychology department at Georgia State University.

The IRA, which sought to reunify Northern Ireland with Ireland, and ETA, a Basque separatist group in Spain, terrorized Europe for a generation. The FARC, a Marxist-Leninist insurgency in Colombia, and the Maoist Shining Path in Peru, did the same in South America. The anti-apartheid ANC in South Africa was deemed a terrorist group by the United States until 2008, though its leader, Nelson Mandela, became South Africa’s president in 1994. In the US, 35 percent of all terrorist attacks between 2010 and 2016 were committed by right-wing groups, according to the START center.(8) The murder of 11 people in a synagogue in Pittsburgh in October of this year focused more attention on the growing problem of far-right terrorism. But in the US, an attack on civilians for ideological reasons is generally only prosecuted as terrorism if it is committed by those affiliated with a foreign terrorist group.(9) American Timothy McVeigh, for example, who killed 168 people when he bombed a federal building in 1995, was never charged with terrorism.(10) And the Trump administration has cut funding for prevention programs targeting domestic right-wing groups.(11,12,13)

Terrorism moves around the globe in waves over time, says Gary LaFree, the former director of START at the University of Maryland. “What makes political violence more common in some periods than others?” he asks. “We don’t know very much about which government policies work.”

On a bright fall afternoon, David Aufsess, a social worker with VAJA, a prevention organization in Bremen, Germany, climbed into a Volkswagen minivan in the Gröppelingen neighborhood. He turned down a broad street lined with restaurants and shops called Little Istanbul. At well over six feet tall with wavy dark hair and a goatee, Aufsess hardly blends in — he stands about a head taller than anyone he meets here. As he passed a vegetable stand, he leaned out the window and waved to a young man. “There are a lot of young people on the streets here,” he says.

DAVID AUFSESS IS A STREET SOCIAL WORKER WITH THE PREVENTION ORGANIZATION VAJA IN BREMEN, GERMANY. HE MEETS WITH YOUNG PEOPLE IN THE COMMUNITIES WHERE THEY HANG OUT AND DEVELOPS A RELATIONSHIP WITH THEM OVER TIME TO HELP THEM FIND ALTERNATIVES TO VIOLENT EXTREMIST GROUPS AND IDEOLOGY. (CHRISTOPH KUBE FOR ORB MEDIA)

Aufsess, a street social worker, spends a lot of time meeting those young people where they hang out, learning about their concerns, gaining their trust and connecting with others. He helps at a nearby school where Salafist Islamic students intimidated classmates four years ago.

VAJA began working with neo-Nazis in the 1980s. That is when the program developed its street social work approach as a way of building trust over time with neo-Nazis. “If you have known someone for two years, you can discuss why someone thinks Jews or foreigners are trash,” he says.

Young people, in particular, can change their ideology, says Aufsess, because they are still forming their ideas. He says they often try out ideologies by challenging their parents or teachers. But if Aufsess develops a relationship with the person, he can engage them about their ideas and encourage them to think critically. Young people, in particular, can change their ideology, says Aufsess, because they are still forming their ideas. He says they often try out ideologies by challenging their parents or teachers. But if Aufsess develops a relationship with the person, he can engage them about their ideas and encourage them to think critically.

Several years ago a mosque in Bremen was closed after a few members left to fight in Syria. Soon, young people from that mosque began asking Imams elsewhere about Jihad, says Esra Basha, project manager at Al-Etidal, a project of Schura Bremen, an Islamic organization that works with mosques throughout the city. Her organization educates young people about religion to make them less vulnerable to recruitment. “The question is not what is Jihad, but why are you asking that? And why is it so important to you?” she says. “We work against ideology, which is very adjustable.”

Some groups go even further. Any ideology that denies pluralism and tolerance must be challenged, says Götz Nordbruch, co-founder of Berlin-based UFUQ.de, which organizes discussion groups in schools. “The red lines are positions that focus on a devaluation of others, positions that are anti-pluralist,” he says. In Germany, ideology is at the root of the problem.

Those who do this work in Indonesia see it differently. Former terrorists there like Harmanto are not less radical than they once were. They have only renounced first-strike violence.

Harmanto’s change was deeply personal. He was on the run for two years before he was captured. The police drove him to his parents’ home and he watched while they searched it. Inside they found hundreds of bullets. “From inside the car I saw my mother crying,” he says. “That is when I thought, ‘I have to change.’” Harmanto was convicted of harboring the mastermind of the Bali bombing and its lead bomb maker and served four years of a six year sentence in prison.

ESRA BASHA AND HER CO-WORKERS AT AL-ETIDAL WORK WITH MOSQUES AND YOUNG PEOPLE IN BREMEN, GERMANY, TO PROVIDE A RELIGIOUS GROUNDING TO HELP PREVENT RECRUITMENT BY TERRORIST GROUPS AND TO DETER YOUNG PEOPLE FROM EXTREMIST IDEOLOGY. (CHRISTOPH KUBE FOR ORB MEDIA)

His change occurred slowly, says Thayep Malik, who manages another restaurant that hires former terrorists when they get out of prison to help them reintegrate into society. The restaurant is part of the Institute for International Peace Building, an Indonesian nonprofit. “There have been so many transformations with him, especially in his willingness to build relationships with other people,” Malik says.

Yet Malik, who has worked for years with Harmanto and other former terrorists, says that they are unlikely to listen to an outsider who tells them that their ideology is wrong. “There is no meeting point between us on ideology,” says Malik. “But we can be unified about the idea of rejecting violence.”

Another former member of Jemaah Islamiyah, Arif Budi Setiawan, who lives in a dirt floor house in rural East Java, renounced violence in prison after seeing how even Christian militia members suffered alongside him. But like Harmanto, he says his beliefs are the same. “In Sharia I did not change,” he says, referring to the fundamental tenets of Islamic law. What has changed is his view of when violence should be used, a change that he writes about online in an effort to prevent others from joining violent groups. “Violence is only for self-defense,” he says.

Sidney Jones, director of the Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict in Jakarta, Indonesia, says it is common to think that radical ideology should not be changed, particularly among the country’s large Muslim organizations. “Here radicalization in defense of the faith is good,” says Jones. In fact, many people believe that those like Harmanto were doing the right thing, she adds. They just went too far.

Despite the stark differences between prevention programs in Germany and Indonesia, they both mirror some of the newest research into how and why people join terrorist groups: The power of social relationships.

Sitting on a stoop across the street from the home that he shares with his wife and six children, Harmanto explains that he was recruited in a Quran study group in high school. Harmanto became close friends with the older boys and was drawn into their circle. “My religious direction was influenced by my friends,” he says.

This process is no different than what most teenagers go through as they find their interests in life, Harmanto says. If his friends were musical, he might have become a musician, he muses, conjuring up an alternative world in which he played the drums rather than killing and maiming tourists. “The more I hung out with them the more I became one of them.”

There are myriad localized reasons that people can be drawn to terrorist groups. In Tunisia, both well-educated and poorly educated people have left to fight with ISIS. In Yemen, Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula touts its development projects on Twitter to gain favor with communities there. Far right groups play on the fear of immigrants in Germany. In the Nordic countries, second and third-generation immigrants who feel they are not accepted in their host countries or by their parents’ culture are most vulnerable, says Magnus Ranstorp, the research director at the Centre for Asymmetric Threat Studies at the Swedish Defense University.

But some key psychological factors likely underlie these local differences, says Horgan at Georgia State. “There are people we call terrorists from vastly different political, ideological and social contexts,” Horgan says. “Their psychology has much more in common than their superficial differences might suggest.”

New research suggests that relationships, like the friendships that drew Harmanto into Jemaah Islamiyah, may be among the most important factors in determining who joins these groups and who stays out of them.(14,15) Julie Chernov Hwang, an associate professor of political science and international relations at Goucher College in the United States, spent half a dozen years interviewing 55 current and former terrorists in Indonesia.

That country’s history of terrorism dates back to the fight for independence in the 1940s. There are some communities where in one family an uncle may have fought in Bosnia and a cousin may have fought in Afghanistan or a brother went to Syria.

“People can join a group because their best friend is in it or their older brother,” says Chernov Hwang, author of Why Terrorists Quit: The Disengagement of Indonesian Jihadists. “They join because they like the feeling of brotherhood.”

Those who work to change ideology in Germany have found similar social relationships at the root of radicalization. Social relationships in school, with sports teams and through religious groups are central to the lives of the young people. “If something is missing then the youngster has to search somewhere else,” says Aufsess. “Youngsters are human, they are always searching for connections.”

Terrorist groups in Germany use online relationships to recruit girls because their social lives are more restricted, says Dantschke, from Hayat. An online recruiter might sympathize with a girl’s conflicts with her parents, for instance, and acts like a big sister, slowly luring the girl into more restrictive and ideological chat groups.

Organizations in both Germany and Indonesia also use social networks to deter people from joining these groups. Dantschke’s organization uses the family structure to help provide a solid relationship for the young person. “Sometimes there is a brother or a cousin or maybe an old friend who refuses to be pushed out of this new life,” she says. “It’s about finding people who can still reach this teenager.”

For Wasiran, his relationship with Harmanto, and the work he does in the restaurant have proven to be the social environment that has shaped his new, less violent way of seeing the world.

WASIRAN WAS AT RISK OF BEING RECRUITED BY A VIOLENT GROUP IN HIS TOWN OF SOLO IN CENTRAL JAVA, INDONESIA. THANKS TO THE WORK HE DOES IN A RESTAURANT WITH HIS NEIGHBOR, FORMER TERRORIST JOKO TRI HARMANTO, HE HAS NOW RENOUNCED VIOLENCE, EXCEPT FOR SELF-DEFENSE. (ANDREAS VINGAARD FOR ORB MEDIA)

Around 10 a.m., as the last customers leave the restaurant and Wasiran and his teenage son and nephew begin closing up, Wasiran takes a break. “This is our place of worship, our place of interaction with friends and our field of good deeds,” he says, explaining that once a month their restaurant serves its food free of charge as a way of giving back to the community — something they call blessed Friday.

This restaurant has become Wasiran’s new community, a place that grounds him in his faith and the lessons he has learned from Harmanto. He may be more likely to stay on that path because of his growing ties to the friends he has made here. Wasiran won’t rule out the possibility that one day his religion may need to be defended with the use of violence, but for now the restaurant has become an anchor for him. “We can share and exchange experiences, whether it's about religion, work, or whatever,” he says. “We can gain knowledge here.”